RDF Это просто. RDF — инструмент для неструктурированных данных

С этой статьи я начинаю совй цикл постов «для новичков» где максимально популярно растолкую понятия веб 3.0. В последствии все статьи перекочуют в вики и будут «изданы» мною в виде PDF книги.

Начнем со средств, и сегодня у нас основа основ - RDF.

Resource Description Framework

- это разработанная консорциумом W3C модель для описания ресурсов, в особенности - метаданных о ресурсах.

RDF это язык описания знаний. Это не совсем XML. то есть совсем не XML , просто синтаксис похож. RDF содержит тройки данных «объект - предикат - субъект». ну пример «Столб имеетВысоту 15м». Вот простейший пример; RDF.:

Имена в RDF бывают двух типов: литералы (просто текст) и URI . URI может быть ссылкой на веб сайт (http://futuri.us) но не обязательно. В целом URI это ссылка на какой-либо объект (не обязательно он имеет свое представление), к примеру urn:isbn:5-3180-0093-2. Это ссылка на книгу " Samba. Руководство системного администратора. Для профессионалов " Эда Бруксбэнка. У этой книги вряд ли есть страничка, но четко и ясно, что этот URI указывает на книгу, и ясно на какую. URI уникально. Потому позволяет привязывать RDF к какому-то единственному объекту.

Editor’s Note: This presentation was given by Jesús Barrasa at GraphConnect San Francisco in October 2016.

Presentation Summary

Resource Description Framework (RDF) triple stores and labeled property graphs both provide ways to explore and graphically depict connected data. But the two are very different – and each have different strengths in different use cases.In this presentation, Dr. Jesús Barrasa starts with a brief , including the origins of the Semantic Web.

A Brief History: The RDF and Labeled Property Graph

Let’s go over a brief history on where these two models come from. RDF stands for Resource Description Framework and it’s a W3C standard for data exchange in the Web. It’s an exchange model that represents data as a graph, which is the main point in common with the Neo4j property graph.It understands the world in terms of connected entities, and it became very popular at the beginning of the century with the article the Semantic Web published in Scientific American by Tim Berners-Lee, Jim Hendler and Ora Lassila. They described their vision of the Internet, where people would publish data in a structured format with well-defined semantics in a way that agents - software - would be able to consume and do clever things with.

Next, persisting RDF - storing it - became a thing, and these stores were called triple stores . Next they were called quad stores and included information about context and named graphs, then RDF stores, and most recently they call themselves “semantic graph database.”

So what do they mean by the name “semantic graph database,” and how does it relate to Neo4j?

The labeled property graph, on the other hand, was developed more or less at the same time by a group of Swedish engineers. They were developing a ECM system in which they decided to model and store data as a graph.

The motivation was not so much about exchanging or publishing data; they were more interested in efficient storage that would allow for fast querying and fast traversals across connected data. They liked this way of representing data in a way that’s close to our logical model - the way we draw a domain on the whiteboard.

Ultimately, they thought this had value outside the ECM they were developing and a few years later their work became Neo4j.

The RDF and Labeled Property Graph Models

Now, taking into account the origin of both things - the RDF model is more about data exchange and the labeled property graph is purely about storage and querying - let’s take a look at the two models they implement. By now you all know that a graph is formed of two components: vertices and the edges that connect them. So how do these two appear in both models?In a labeled property graph, vertices are called nodes, which have a uniquely identifiable ID and a set of key-value pairs, or properties, that characterize them. In the same way, edges, or connections between nodes – which we call relationships - have an ID. It’s important that we can identify them uniquely, and they also have a type and a set of key value of pairs - or properties that characterize the connections.

The important thing to remember here is that both the nodes and relationships have an internal structure, which differentiates this model from the RDF model. By internal structure I mean this set of key-value pairs that describe them.

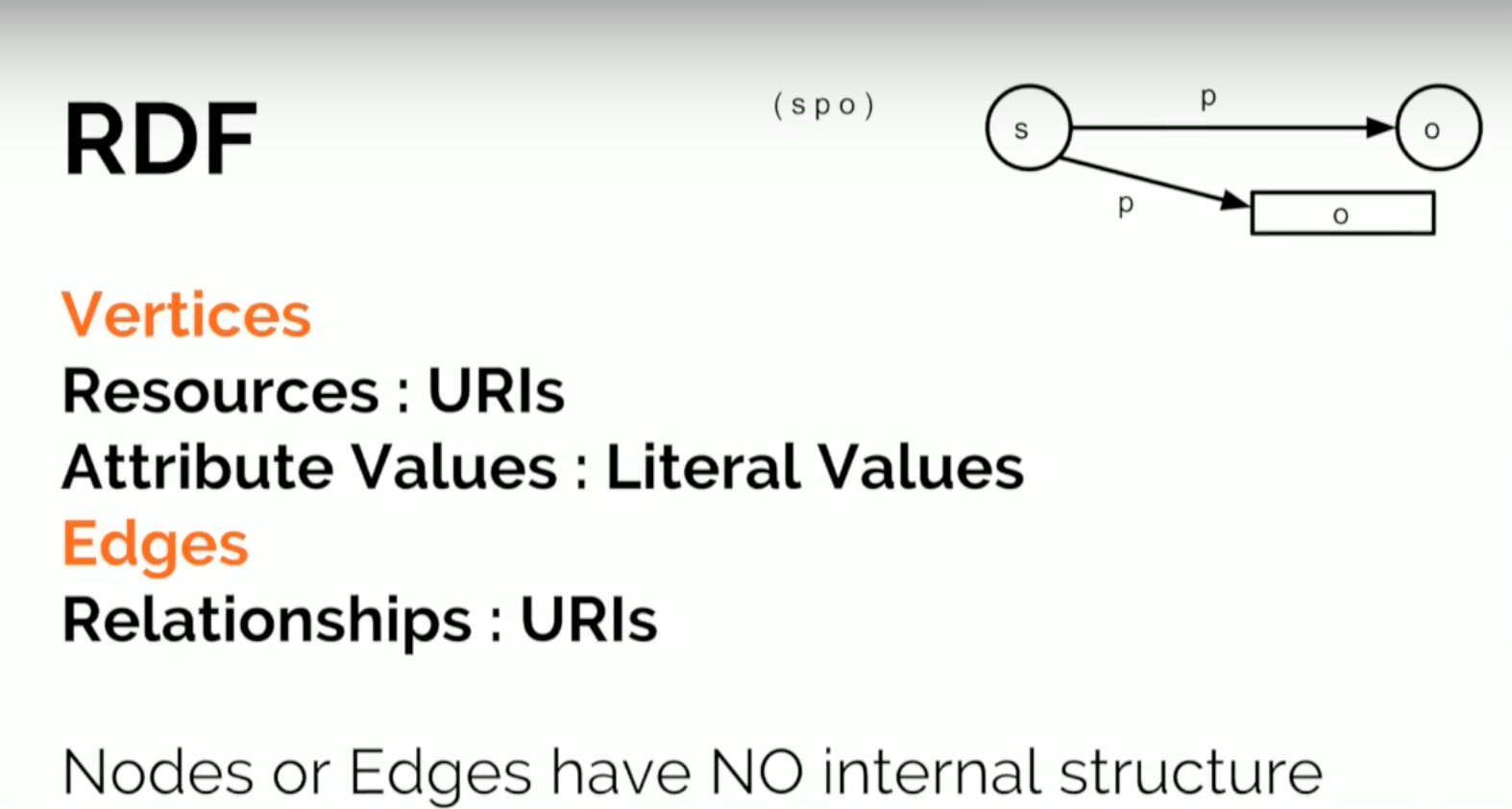

On the other hand, in the RDF model, vertices can be two things. At the core of RDF is this notion of a triple, which is a statement composed of three elements that represent two vertices connected by an edge. It’s called subject-predicate-object . Subject will be a resource, or a node in the graph. The predicate will represent an edge – a relationship - and the object will be another node or a literal value. But here, from the point of view of the graph, that’s going to be another vertex:

The interesting thing to know is that resources (vertices/nodes) and relationships (edges) are identified by a URI, which is a unique identifier. This means that neither nodes nor edges have an internal structure; they are purely a unique label. That’s one of the main differences between RDF and labeled property graphs.

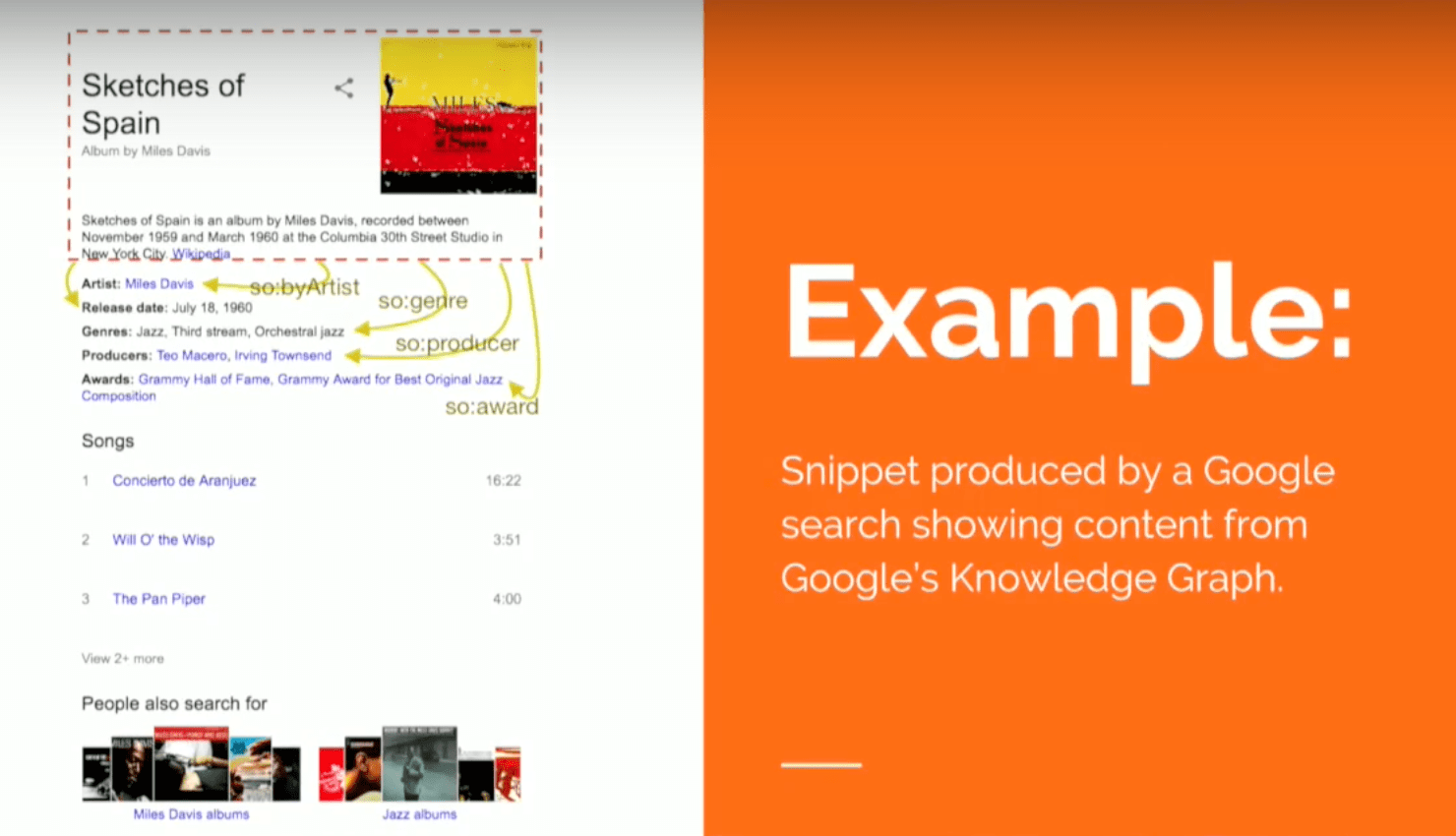

Let’s take a look at an example to make this a bit more clear:

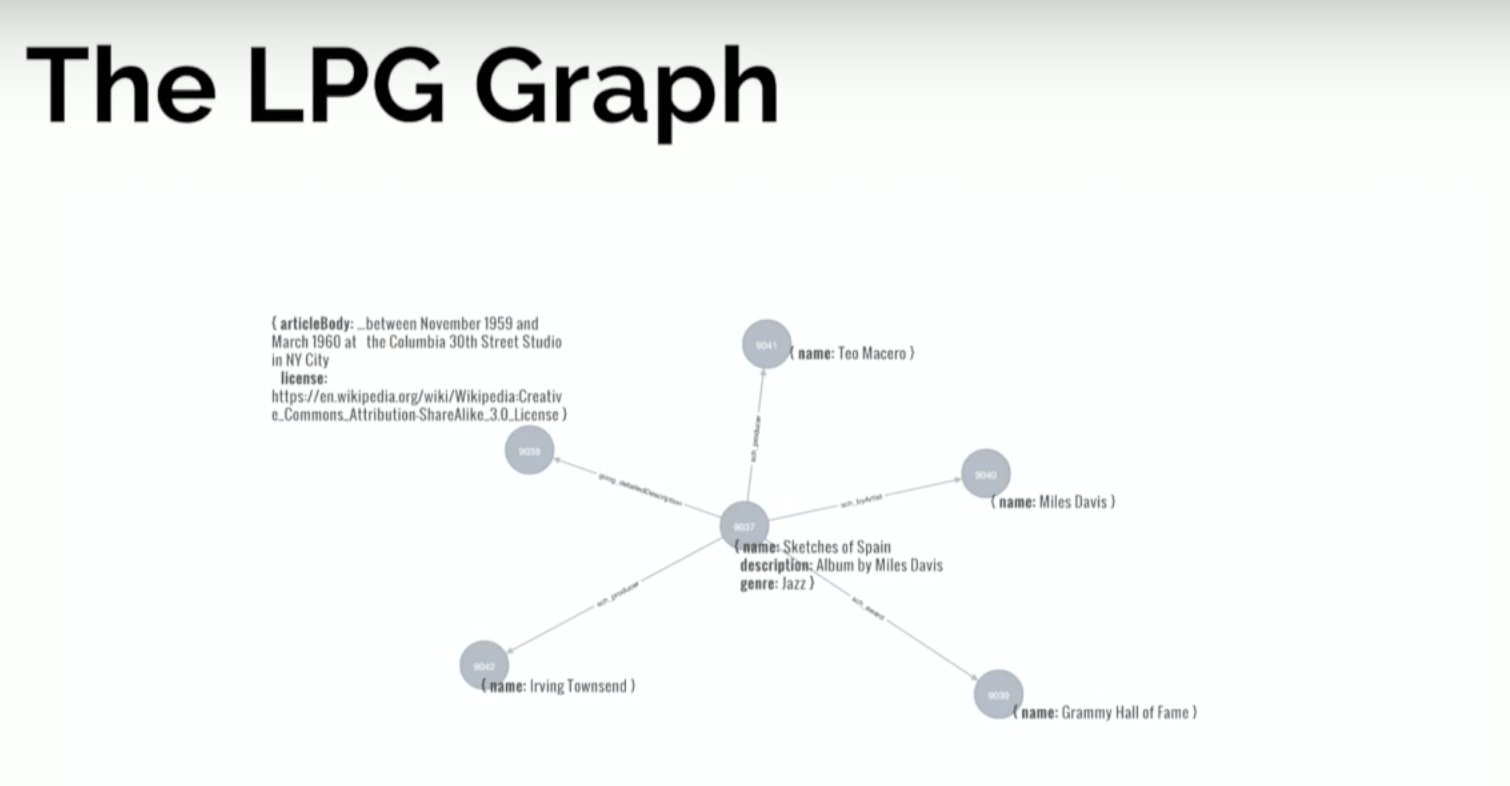

Here’s a rich snippets that Google returns when you do a search for Sketches of Spain , which is one of my favorite albums by Miles Davis. This search returns a description of the album with things like the artist, the release date, the genre, producers and some awards. I’m going to represent this information in both models below.

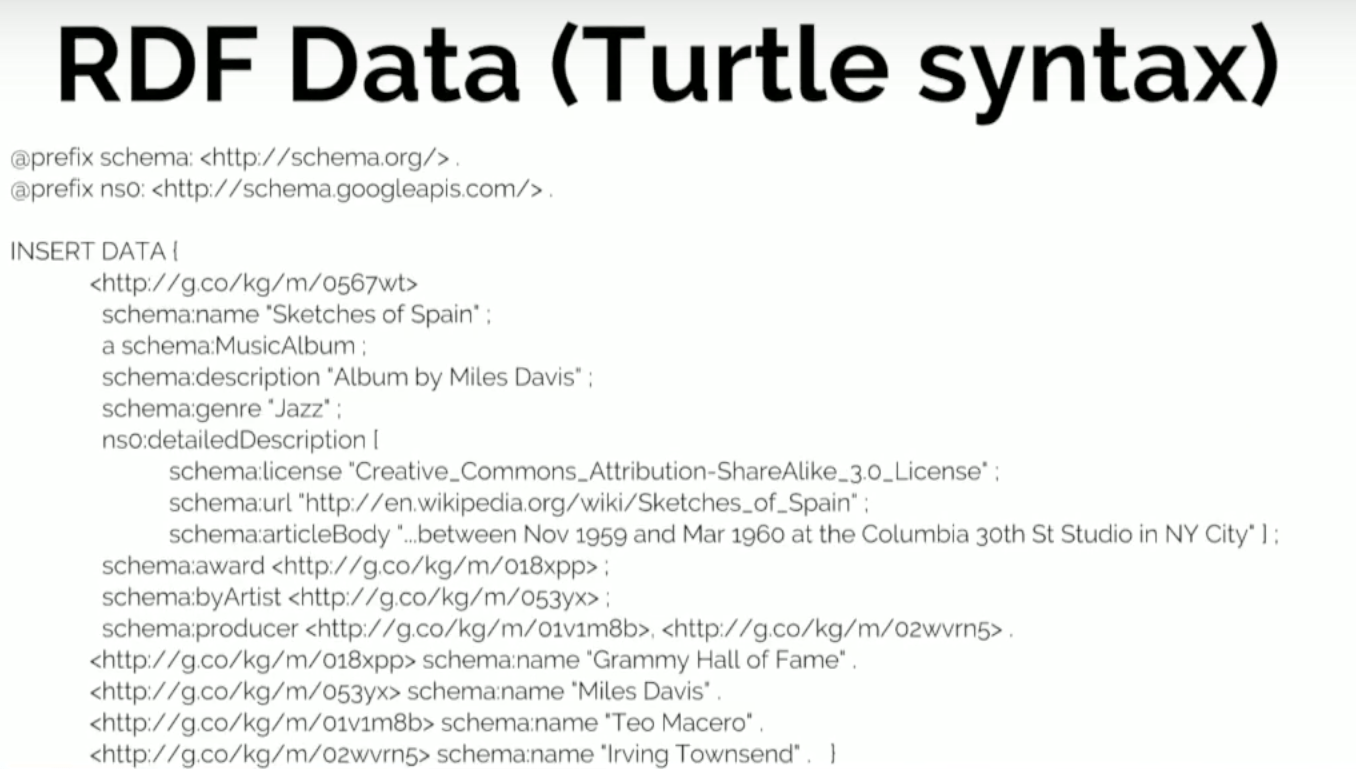

Below is one of the possible serializations of RDF called Turtle syntax:

You can see that the triples are identified by a URI, which is the subject. The predicate is the name and the object will be Sketches of Spain , which together is a sequence of triples. So these are the kinds of things you will have to write if you want to insert data in a triple store.

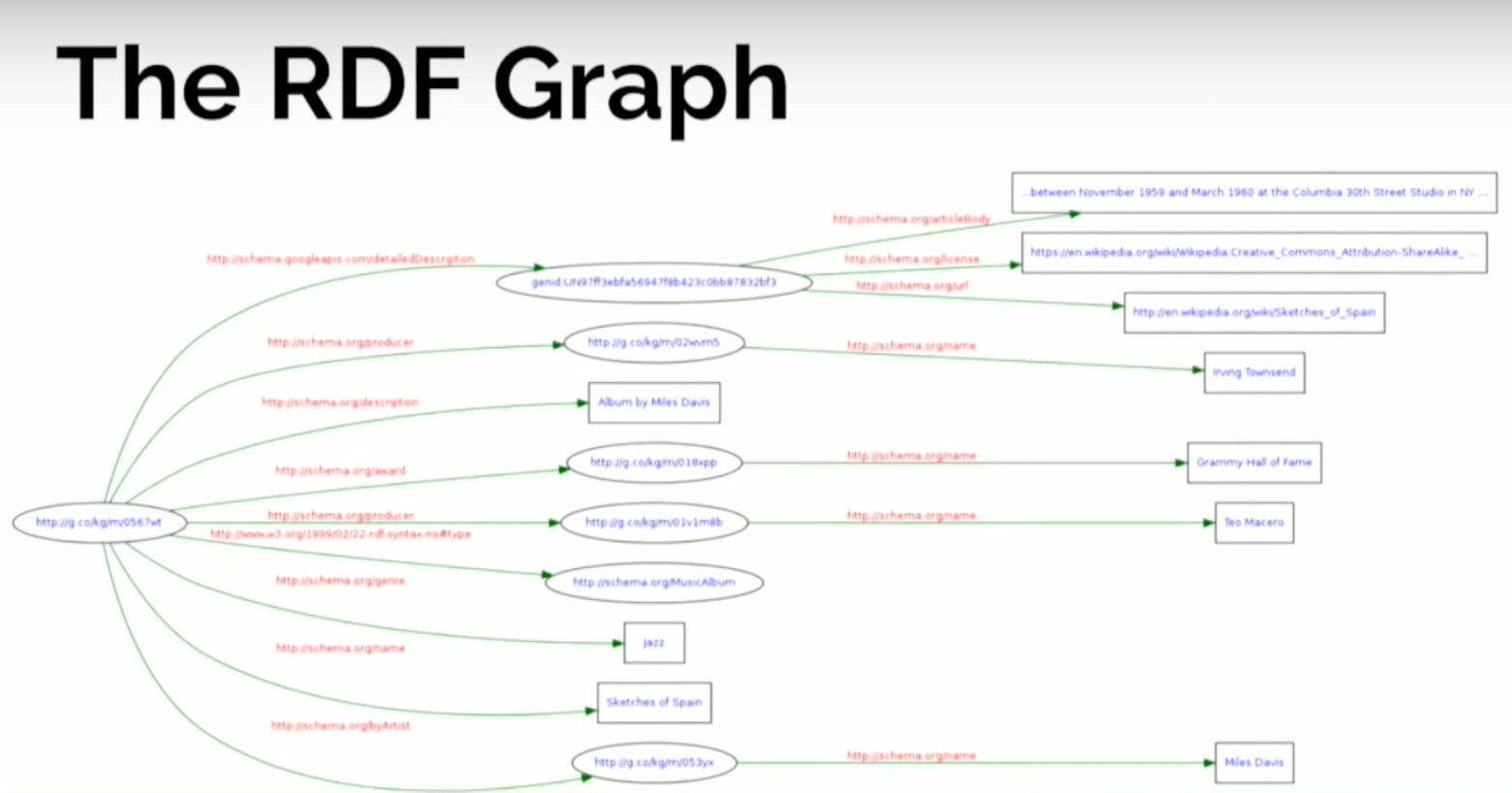

Let’s look at how this information is displayed graphically:

The nodes on the left represent the album, which has a set of edges coming out of it. The rectangles represent literal values - the description: album about Miles Davis, the genre, the title - and it has connections to other things that are in ellipses that represent other resources (i.e., other nodes in the graph) that have their own properties and attributes.

What this means is that by representing data in RDF with triples, we’re kind of breaking it down to the maximum. We’re doing a complete atomic decomposition of our data, and we end up finding nodes in the graph that are resources and also literal values.

Now let’s look at it from the point of view of the labeled property graph. What I’ve created below is a sequence of statements that contain exactly the same information as the Turtle syntax above:

The semantics are the same. There’s no standard serialization format, or a way of expressing a labeled property graph, but rather a sequence of CREATE statements do the job here.

We create a node, which is more obviously represented with a parenthesis, and then the attributes - or the internal structure - in the curly bracket: the name, the description and the genre. Likewise, the connections between nodes are described with hard brackets.

Below is what the labeled property graph looks like:

The first impression is that it’s much more compact. Even though it has certain elements in common with the RDF graph, it’s completely different because nodes have this internal structure and values of attributes don’t represent vertices in the graph.

This allows for a much more reduced structure. But we still have the album at the center, which is connected to a number of entities, but the title, name and description aren’t represented by separate nodes. That’s a first distinction.

Sometimes there’s confusion when we compare the two models. If you have a graph with two billion triples, how do the two compare in terms of nodes, for example? If we take a graph with n nodes with five properties per node, five attributes, five relationships and five connections, we would get 11 triples per node in a labeled property graph.

Again, I’m not comparing storage capacity, but keep in mind that when you have a 100 million triple graph (i.e., RDF graph), that’s an order of magnitude bigger than a labeled property graph. That same data will probably be equivalent to a ten-million-node labeled property graph.

Key Differences Between RDF and Property Graphs

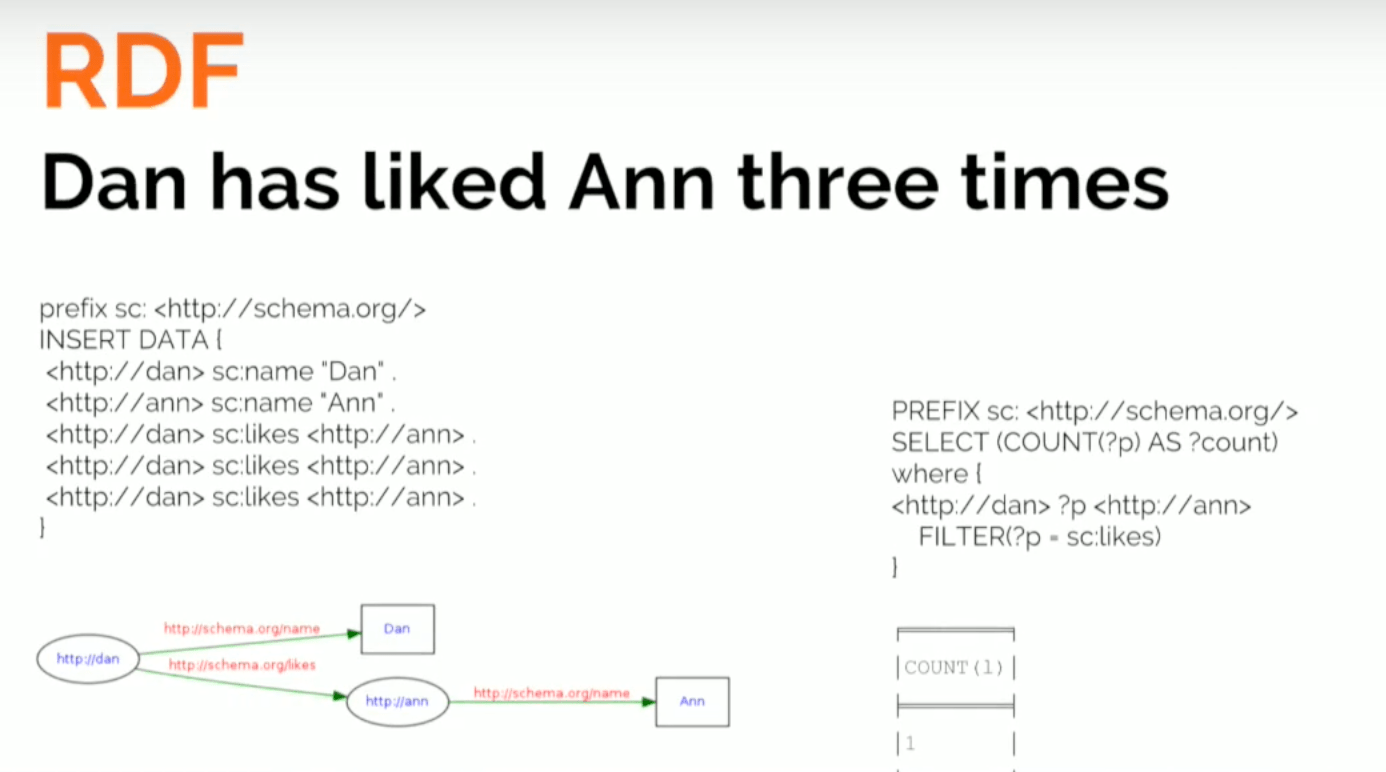

Difference #1: RDF Does Not Uniquely Identify Instances of Relationships of the Same Type

Now that we know a bit more about the two models, let’s compare differences in terms of exclusivity.The first one is quite important, and that is the fact that in RDF it’s not possible to uniquely identify instances of a relationship. In other words, we can say: it’s not possible to have connections of the same type between the same pair of nodes because that would represent exactly the same triple, with no extra information.

Let’s look at the following as an example, a labeled property graph and an RDF graph in which Dan cannot like Ann three times; he can only do it once:

We create a node called Dan that LIKES Anne . I repeat that Dan likes Anne two more times, and I end up with a graph that has three connections of type LIKES between Dan and Ann. Good.

Not only can we visualize this in a helpful way, but we can also query it to ask, “How many times does this pattern appear in the graph?” which returns a count of three.

Now let’s try to do the same in RDF using SPARQL:

What insert a statement that says Dan has name Dan, Ann has name Ann and Dan LIKES Ann, which we repeat three times. But see the graph that we get instead (above).

We have the values of the properties as vertices of the graph, and we have Dan with name Dan. We have Ann with name Ann, and we have a single connection between them, which is sad, because Dan liked her three times.

If I do the count again searching for this particular triple pattern, and I do the count, I get one. The reason for that is it’s not possible to identify unique instances of relationships of the same type with an RDF triple store.

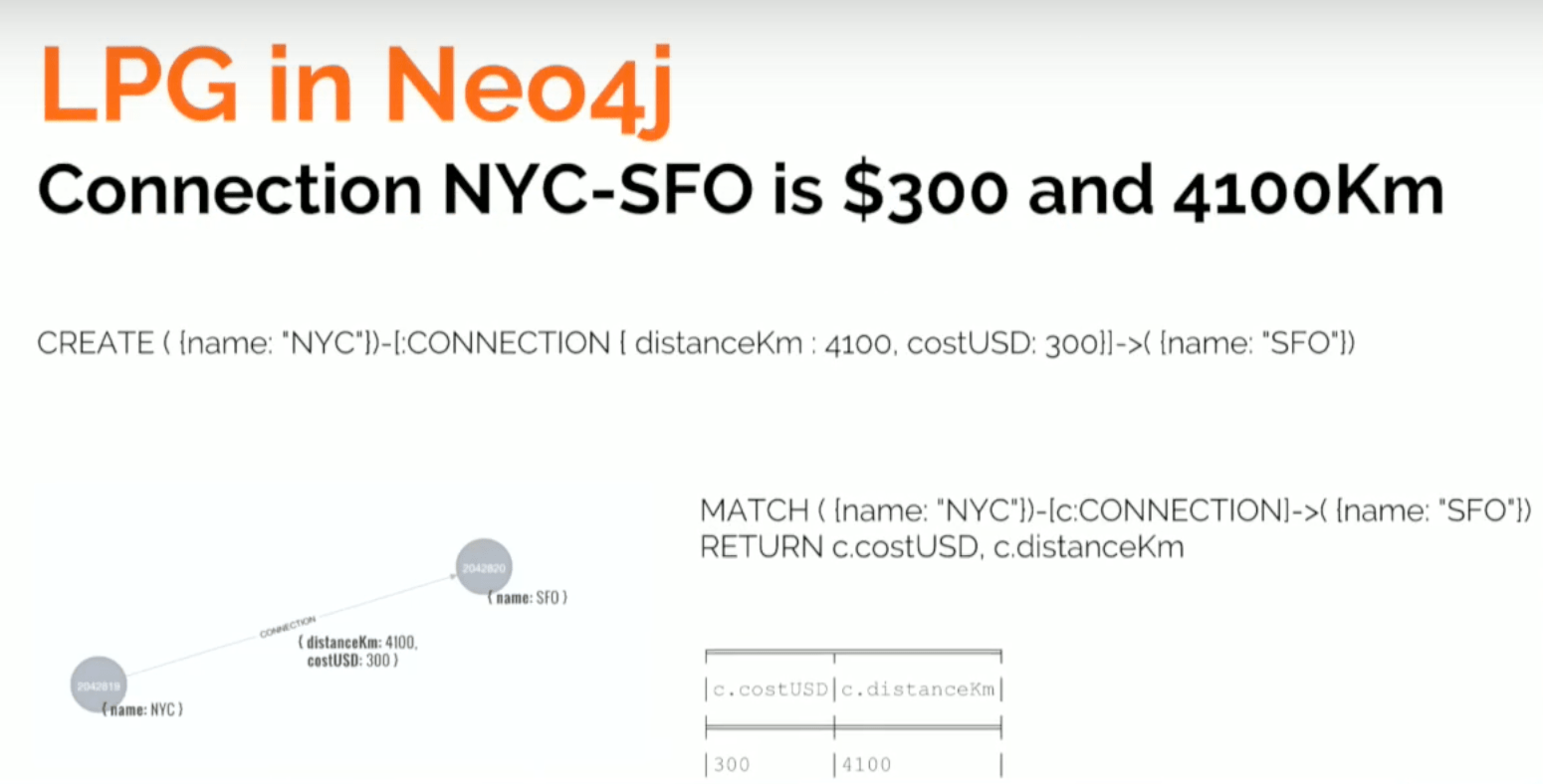

Difference #2: Inability to Qualify Instances of Relationships

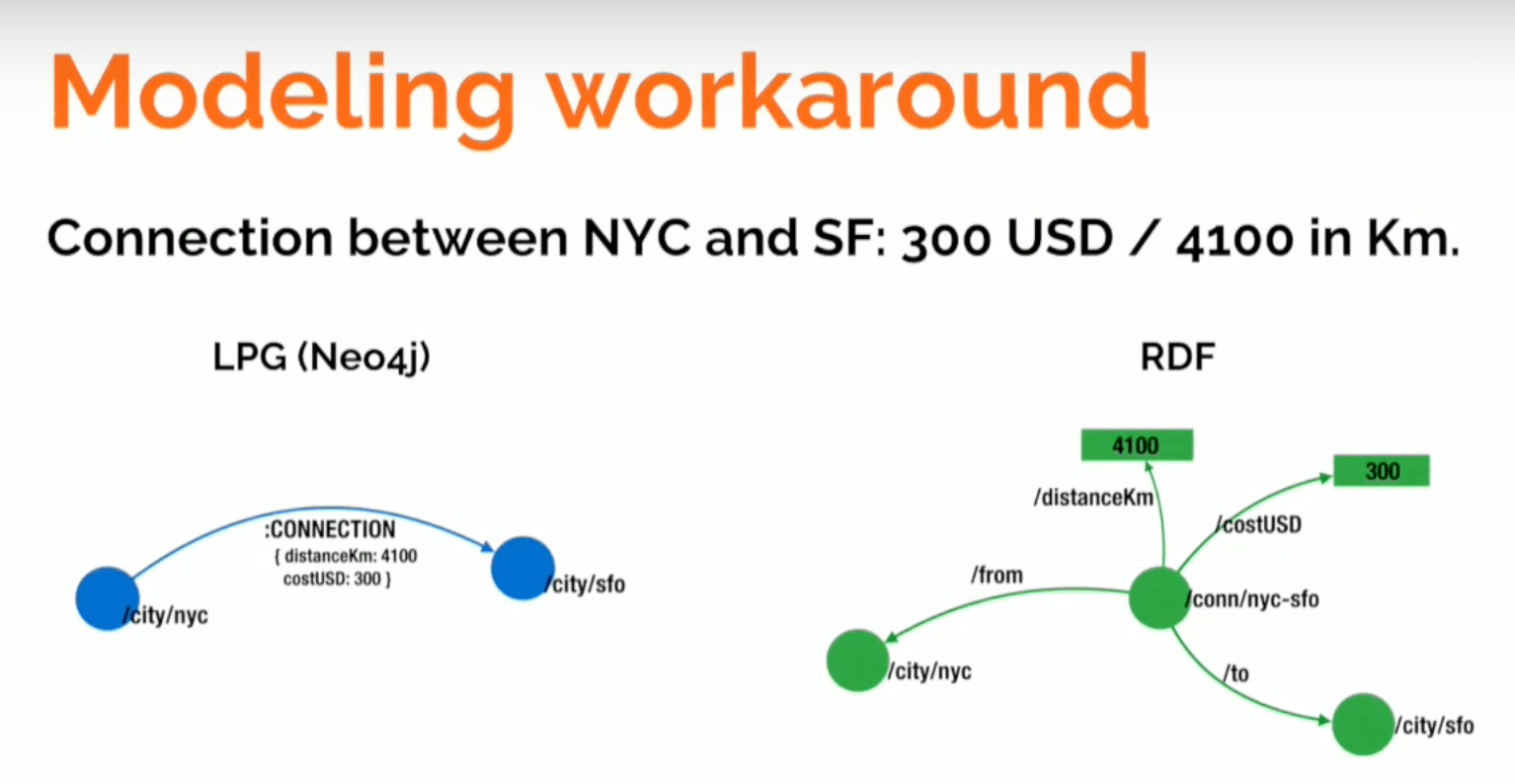

Second, because you can’t identify these unique instances in RDF, you cannot qualify them or give them attributes. Let’s take a look at another example that explores flights between New York City and San Francisco:

It costs $300 and is a total of 4,100 kilometers. Again, this statement can be expressed in Neo4j’s graph query language, Cypher, saying that there’s a connection between New York City and San Francisco, and that the connection has two attributes: the distance and the cost in dollars.

We produce a nice graph and can query the cost and distance of the connection to return two nodes.

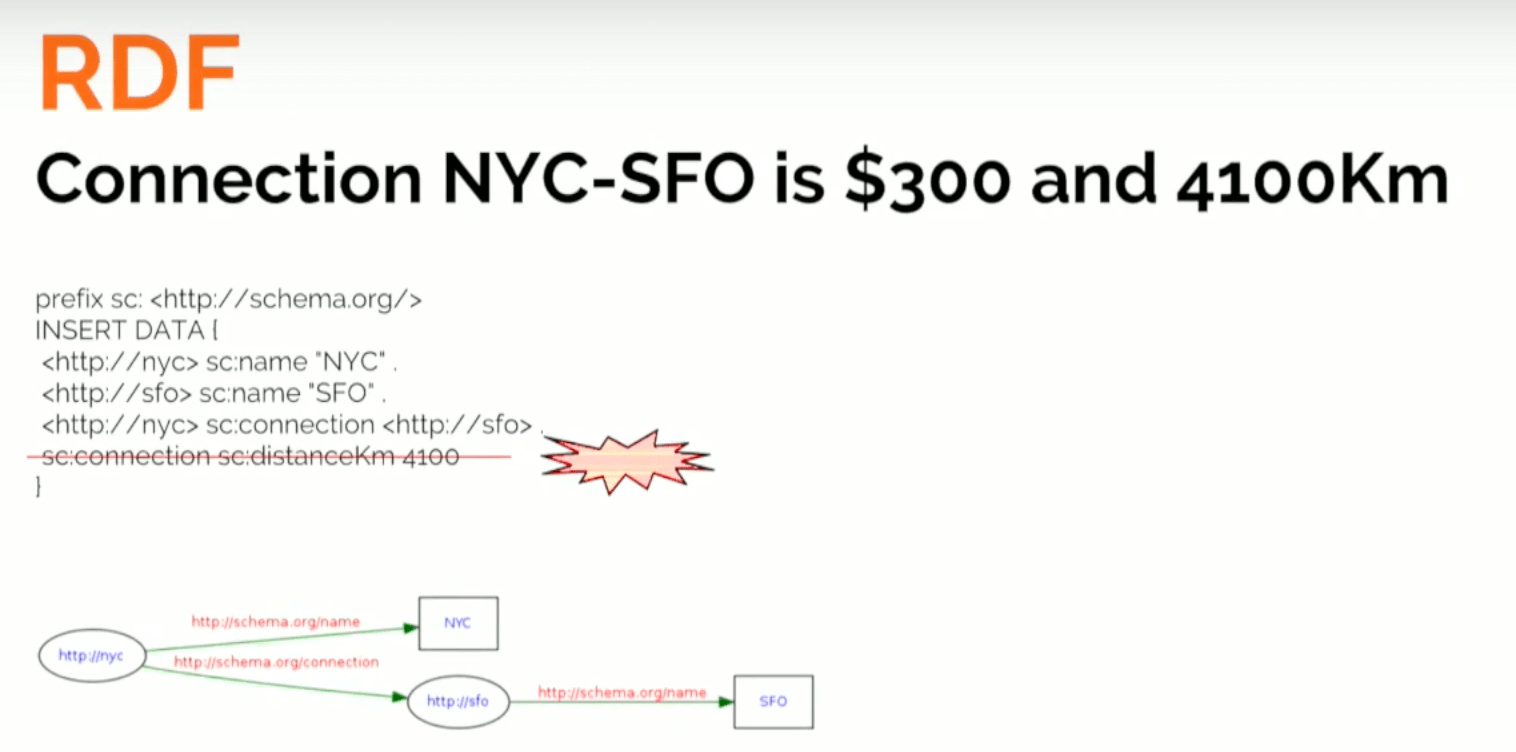

If I try to do the same in RDF, I encounter a problem:

In this query, we say there’s a city called New York, a city called San Francisco, and a connection between them.

But how do I state the fact that this connection has a cost? I could try to say something like, “Connection has a distance.” But which connection? That would be a global property of the connection, so you can’t express that in RDF. As you can see above, here’s the graph that this type of SPARQL query produces.

RDF Workarounds

There are a few alternatives for these weaknesses in RDF.One of them is a data modeling workaround, but we’re going to see that this is the same problem we experience with a . What happens when we have these many-to-many relationships - people knowing people, and people being known by others? This provides an entity-relationship model, but then you have to translate this into tables with several JOINs.

Because the modeling paradigm doesn’t offer you a way to modeling these types of relationships, you have to use what you have on hand and represent it the way you can. And as you know, the problem is that this starts building a gap between your model as you conceive it, and the model that you store and query. There are two alternate technical approaches to this problem: reification and singleton property.

Below is one RDF data modeling workaround, which is the simple option:

Because in RDF we don’t have attributes in relationships, we create an intermediate node. On the left is what I can do in the labeled property graph. Because we can’t create such a simple model in RDF, we create an entity that represents the connection between New York and San Francisco.

Once I have that node, I can get properties out of it. This alternative isn’t too bad; the query will be more complicated, but okay.

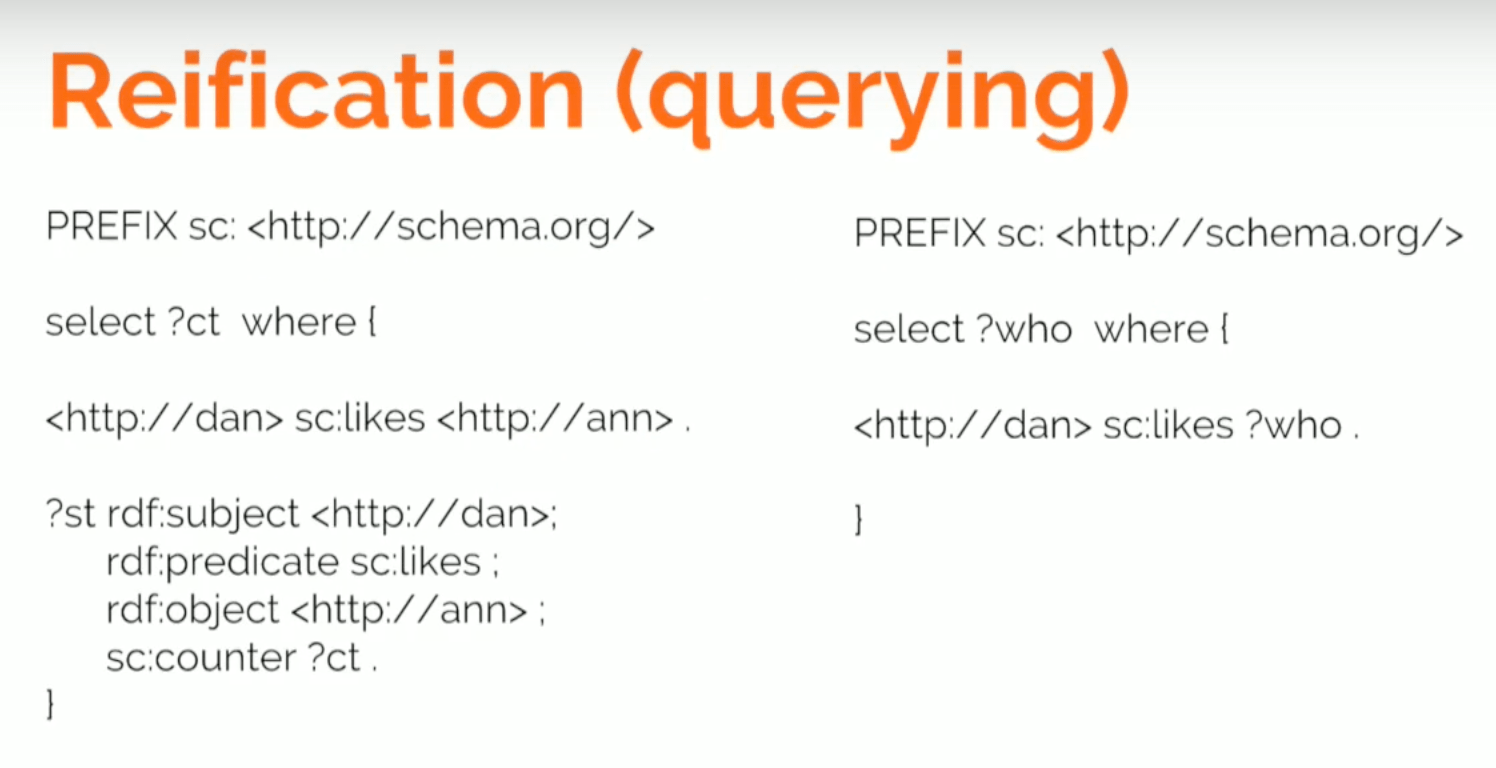

Now let’s take a look at reification, which - as you can see - isn’t very readable:

We still have Dan with with name Dan , and Ann with name Ann with a connection saying that he likes her.

With reification, we create a metagraph on top of our graph that represents the statement that we have here. We create a new node that represents a statement and points at the subject Dan, at the object Ann, and at the property stating the fact that he likes her. Now that I have an object - a node - I can add a counter, which tells us three.

This is quite ugly. On the one hand, you can still query who Ann likes:

But if you want to query “how many times,” you have to go look at both the graph and the metagraph. So if Dan likes Ann, then look at the statement that connects Dan and Ann and get the counter.

Now, imagine if you need to update that. You would have to say, “Dan has liked her one more time.” You wouldn’t come and say, “Add one more” because that doesn’t add more information. You will have to come and say, “Grab a pattern, take the value in the counter, increase it by one, and then set the new value.”

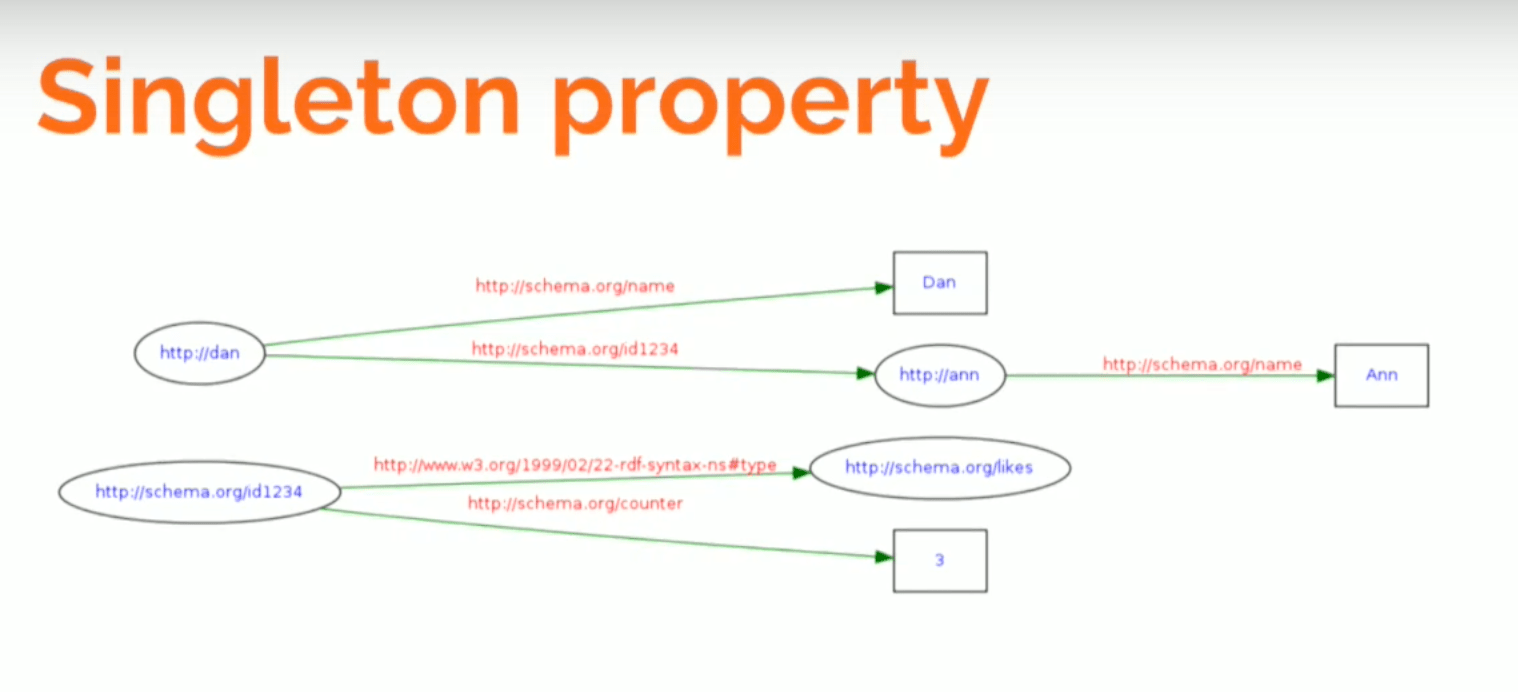

The Singleton property is another modeling alternative pretty much in the same vein:

You have your original model - Dan with his name who likes Ann, with her name. You can give this relationship a unique name, ID1234 , which allows us to describe it. We can say it’s an instance of likes and I can give it a counter of three.

Again, I’m building a metamodel that - while more compact than the reification model - still doesn’t allow you to ask, “Who does Dan like?” You have to ask, “Who does Dan 1234 ?” which is the type like .

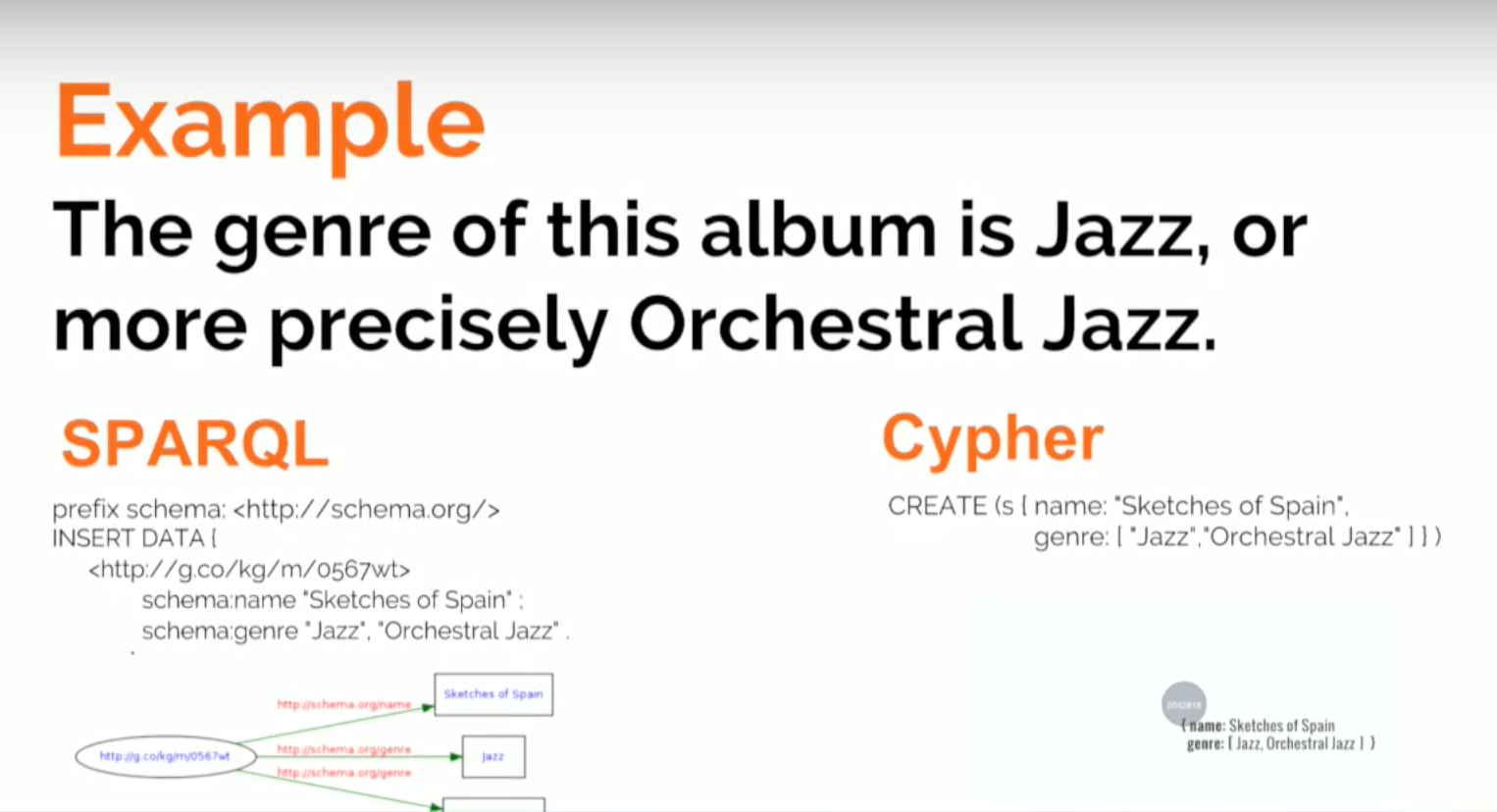

Difference #3: RDF Can Have Multivalued Properties and the Labeled Property Graph Can Have Arrays

In RDF you can have multi-value properties - triples where the subject and predicate are the same but the object is different - which is fine. In the labeled property graph you have to use arrays, which is the equivalent.

In the snippet we had before, we had an album that had two values for the genre property: jazz and orchestral jazz. That’s easy to express in triples, and in Cypher you will need to use an array - not too bad.

Difference #4: RDF Uses Quads for Named Graph Definition

Another difference is this notion of quad, which has no equivalent in labeled property graphs. You can add context or extra values to triples that identifies them and makes it easy to define subgraphs, or named properties.We can state that Dan likes Ann in graph one and Ann likes Emma in another graph:

RDF & Labeled Property Graph Query Languages

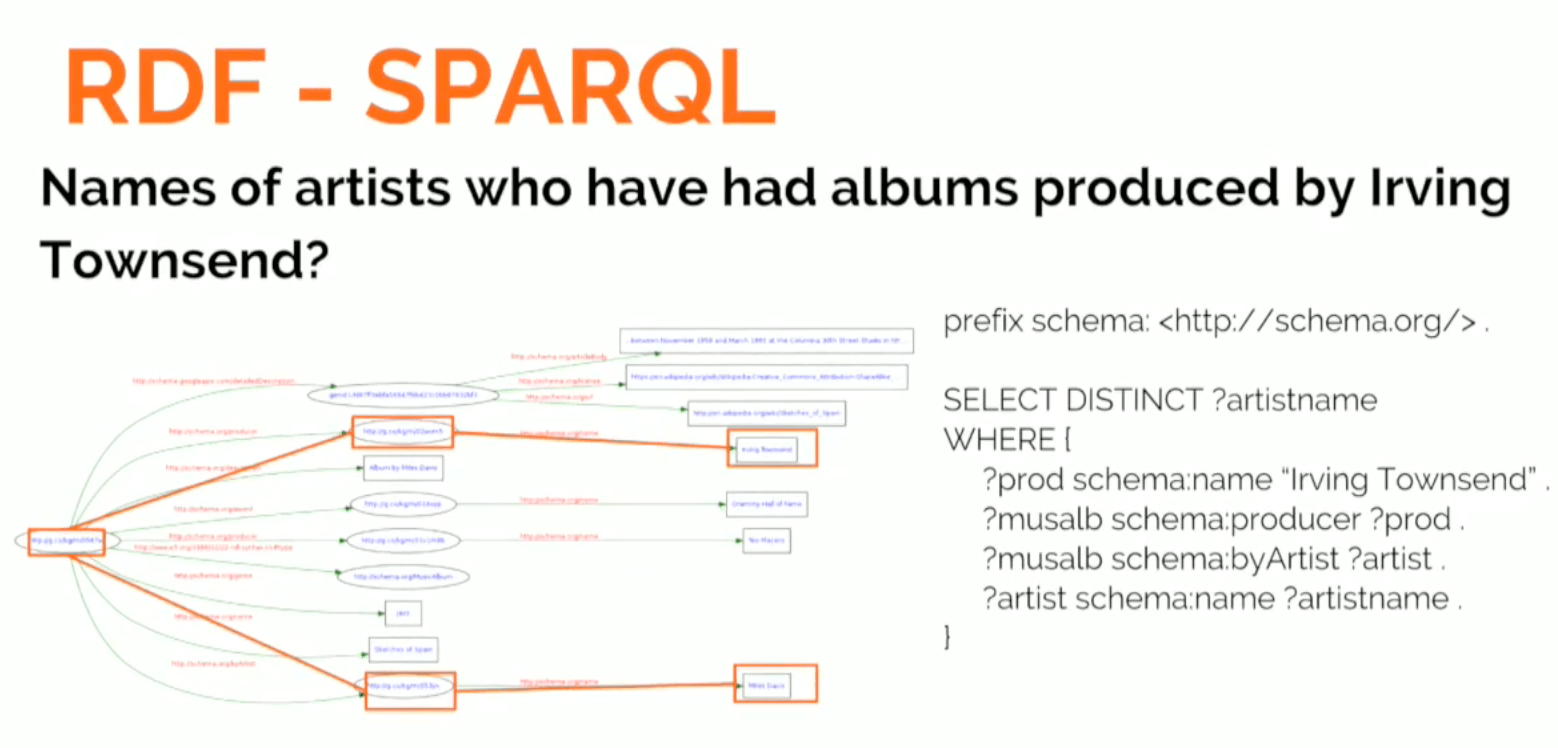

The two different models also rely on different database query languages.Because of the atomic decomposition of the data and RDF, you typically have longer patterns when you perform queries. Below is a query that has the names of artists with albums produced by Irving Thompson:

You have four patterns, each of which represents each of the edges in the more compact labeled property graph. But this isn’t what I would call an essential differentiator.

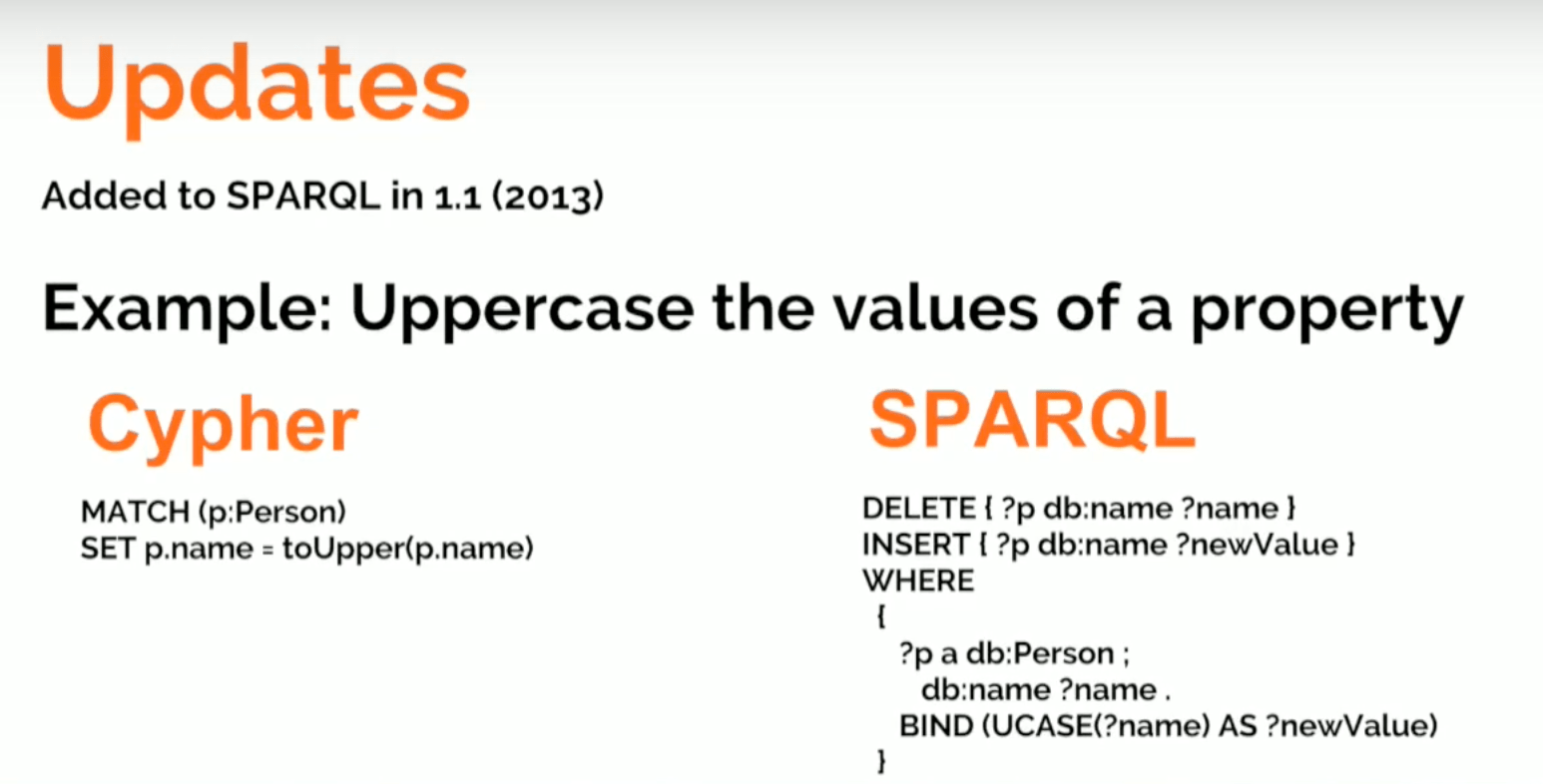

There were a few recent updates to both the SPARQL and Cypher query languages:

Something like uppercasing the values of a property in Cypher is very SQL-like and simple.

You can much a person and attribute name to uppercase , whereas in SPARQL you will have to MATCH it, BIND it to a variable, do the uppercase , and then do the insertion and the deletion because we can have multiple values. So by updating you need to delete the previous value, unless you want to keep both of them.

RDF & Labeled Property Graph Data Stores

RDF stores are very strongly index-based, while Neo4j is navigational. It implements index-free adjacency, which means that it stores the connections between connected entities, between connected nodes, in disks.This means that when you query Neo4j, you’re actually chasing pointers instead of scanning indexes. We know that index-based storage is okay for queries that aren’t very deep, but it’s very difficult to do something like path analysis. Compare that to Neo4j, which allows you to have native graph storage that is best for deep or variable-length traversals and path queries.

It’s fair to say that triple stores were never meant to be used in operational and transactional use cases. They should be used in mostly additive, typically slow-changing - if not immutable - datasets. For example, the capital of Spain is Madrid, which isn’t likely to change. Conversely, Neo4j excels in highly dynamic scenarios and transactional use cases where data integrity is key.

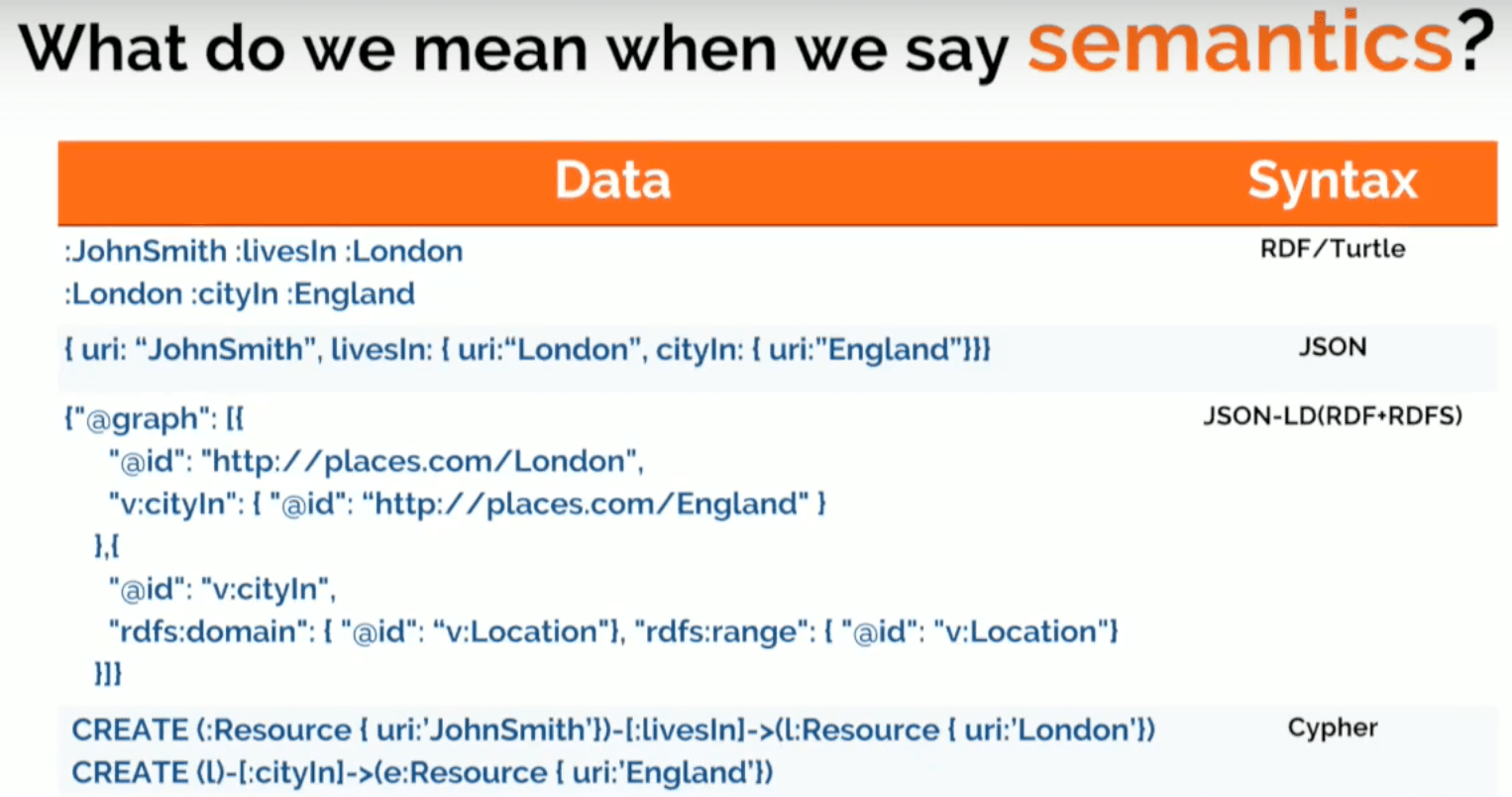

A Comparison: Semantics

The first two lines are on the front end of RDF in total notation, saying that John Smith lives in London and that London is a city in England. The second one is a fragment of JSON that could easily represent the same information. The third one is JSON-LD and includes both the data and the ontology, and the final one is a fragment of Cypher.

Semantics can mean two things in the RDF world. The first is the idea of vocabulary-based semantics. Because you can identify relationships with URIs, you can define agreed-upon vocabularies like Schema.org and Google Knowledge Graph (GKG) . This covers most of the usage of RDF today.

The other meaning is inference-based semantics, which is rule-based - including OWL. We use this when we want to express what the data means so that I can infer facts, do some reasoning or check the consistency of the dataset.

Let’s look at a couple examples. The first example provides a simple pair of facts: John lives in London. London is in England. You can express this with two RDF triples:

:JohnSmith:livesIn:London:London:locationIn:England

Now you run a query: who lives in England? You can express that in SPARQL:

SELECT ?who

WHERE { ?who:livesIn:England }

But it returns zero results because you have to say:

X:livesIn ?city ^

?city:cityIn ?ctry

=> ?x:LivesIn ?ctry

If someone lives in a city and the city is in a country, then you live in the country. But no one’s going to figure that out if you don’t make it explicit in a rule, and this is an example of how you have to make the semantic explicit. The real question is: are your semantics explicit?

If we ask the question again, now that we have defined our rule, it will return John Smith.

Below is another example that shows importing data from two data sources into a triple store. There are two facts coming from datasource1: Jane Smith’s email is [email protected], and her Twitter handle is @jsmith. This can look like the following two triples:

:JaneS1:hasEmail "[email protected]"

:JaneS1:hasTwitterHandle "@jsmith"

Now we get another pair of triples from another data source that says: Jane Smith’s email is [email protected] and her LinkedIn profile is “http://linkdn.com/js.” Again, the two triples below look like this:

:js2:hasEmail "[email protected]"

:js2:hasLnkdnProfile "http://linkdn.com/js"

Next you put it into the RDF graph thinking that semantics are going to do the magic. You ask the question: What’s the LinkedIn profile of the person tweeting as @jsmith? The SPARQL query looks like this:

SELECT ?profile

WHERE { :hasTwitterHandle "@jsmith" ; :hasLnkdnProfile ?profile . }

But again you get no results, because - like in the previous case - you have to say that the email address is a unique identifier and therefore you can infer that if two resources have the same email, you can derive that they’re the same and can be expressed with a rule like this one:

X:hasEmail ?email ^

?y:hasEmail ?email

=> ?x owl:sameAs ?y

You can also express this more elegantly in OWL, which would look like this:

:hasEmail rdf:type

owl:InverseFunctionalProperty

?prop a owl:InverseFunctionalProperty ?p^

?x ?p ?al

=> owl:sameAs ?y

An inverse functional property is a primary-key-style property. It’s not exactly the same because a primary key is a kind of constraint that would prevent you from adding data to your database if there’s another one with the same value.

Here, you can add data without any problem. But if we find two that have the same value, we’re going to think that these two are the same.

Even if we express this in a more declarative way, these are the semantics of an inverse functional property. Basically if two values have the same value, I can derive that they are the same. We re-run the query and this time it will return Jane Smith’s LinkedIn profile.

It’s all about making the data explicit. There’s really no magic here; RDF is just a way of making data more intelligent and making your semantics explicit. Below is a quote from Tim Burners-Lee that speaks to this:

A Demo: How Do We Get to a Semantic Graph Database?

I’m going to show features and capabilities in Neo4j that are typically from RDF as stored procedures and extensions. Hopefully, they’ll make their way into the APOC library soon.So what are the takeaways from this demo? The first one was mentioned in the presentation by the Financial Times, an organization that made the transition from RDF to a labeled property graph.

They thought they needed a linked semantic data platform to connect their data, but what they actually needed was a graph. So always ask yourself what kind of features you need. Is it about the inferencing? Is it about semantics? Or is it just a graph?

If you store your data in RDF and query it in SPARQL, you’re not semantic - you have a graph. In most of the use cases, you find yourself not using as much of OWL and all the semantic capabilities as you would, because you know it’s extremely complex and it results in performance issues. If you’re working with a reasonably-sized dataset, don’t expect it to finish the query.

We also know that publishing RDF out of Neo4j is trivial, which is the same with importing RDF. The code is under 100 lines and is available on Github . It’s a really simple task.

And I’ve also shown that inference doesn’t require OWL. In the end, semantics (inference) is just data-driven, server-side logic, typically implemented as rules. You’re putting some intelligence close to your data that’s in turn driven by an ontology. And if you manage to balance expressivity and performance without falling into unneeded complexity, then it may be a useful tool.

I’m not going to criticize OWL because its own creators discuss why it’s not being adopted. It’s definitely not taking off, and I think one of the reasons is because it can be overkill for many use cases.

Формат RDF может быть нескольких основных модификаций:

- Расширение RDF (полн. Resource Description Framework ) представляет собой платформу для описания web-ресурсов. Основная область практического применения данного формата - представление данных о ресурсах в веб. Содержит набор структурированных данных, включая метаданные, карту сайта, информацию о журнале обновления, описание отдельных страниц сайта, ключевые слова.

Ключевым стандартом, с помощью которого реализовано представление RDF модели является W3C.

Основной целью разработки расширения RDF преследовалось создание единого (универсального) синтаксиса языка описания всего многообразия Интернет-ресурсов. Он объединяет , и N3 форматы представления данных, а также RSS и FOAF интернет-технологии.

Для сохранения настроек и конфигурации интерфейса, RDF файл может активно использоваться различными браузерами, например, Firefox .

- RDF файл - результат генерации PowerProducer , коммерческого программного продукта (разраб. CyberLink), широко применяемого для обработки цифрового видео-контента и прямой его записи непосредственно на оптический носитель.

RDF - это сжатый по определенной технологии файл, представляющий собой образ диска. Расширение невозможно открыть ни одной другой утилитой кроме PowerProducer .

- RDF расширение также может быть ассоциировано с одним из компонентов системы автоматизированного проектирования (САПР) ReluxCAD - комплексом, специально предназначенным для моделирования источников света, как составляющих целостных систем освещения. Позиционирование, яркость, основные технические характеристики - это лишь самый незначительный перечень принципиальных параметров, которые может включать RDF файл. RDF формат зачастую применяется комплексно с форматами и , являющимися “родными” для САПР AutoCAD .

- расширение RDF - файл-отчет в ArcGIS , стандартизованной системе статистического учета, используемой различные ГИС-решения. RDF файл представляет собой структурированный набор данных в виде цифровых таблиц. ArcGIS-отчеты генерируется в специальном программном модуле Report Designer . Для просмотра подобной информации можно пользоваться компонентой Report Viewer .

- RDF формат (полн. Oracle Report Definition File ) может выступать в качестве крупноформатной таблицы-отчета, используемой в СУБД Oracle . По своей структуре RDF файл представляет набор данных, содержащий различные SQL-запросы, необходимые для фактической генерации отчета и обработки его в одном из универсальных форматов ( , и.т.д).

Программы для открытия RDF файлов

В зависимости от своего практического назначения и конкретной модификации, RDF расширение может быть сгенерировано и открыто для редактирования с использованием следующих программных комплексов:

Для случаев, когда RDF файл представляет собой платформу для описания web-ресурсов, можно воспользоваться следующими программными утилитами:

- в ОС Windows используются Altova XMLSpy , Mozilla SeaMonkey , Firefox , Liquid Technologies Liquid XML Studio и SyncRO Soft oXygen XML Editor ;

- на базе ОС Mac RDF будет доступен с применением все тех же программных плагинов Mozilla SeaMonkey и SyncRO Soft oXygen XML Editor .

Примечательно, что расширение адаптировано и для использования на платформе Linux c помощью интернет-браузера Firefox .

Когда RDF файл применяется для обработки цифрового видео-контента и прямой записи непосредственно на оптический диск, может быть использована утилита CyberLink PowerProducer 5.5.

Если RDF формат используется в качестве компоненты системы автоматизированного проектирования (САПР), специально предназначенной для моделирования источников света, как составляющих целостных систем освещения, то для открытия файла может быть задействован комплекс ReluxCAD .

Для случаев, когда RDF расширение ассоциируется файлом-отчетом в ArcGIS (стандартизованной системе статистического учета, используемой различные ГИС-решения), воспроизвести файл можно с помощью программных модулей Report Designer или Report Viewer ;

Когда RDF формат выступает в качестве крупноформатной таблицы-отчета, используемой в СУБД, он будет доступен с помощью Oracle .

В случае если при воспроизведении формата возникает ошибка: либо поврежден или заражен исходный файл, либо осуществляется открытие RDF файла с применением некорректной программной утилиты.

Конвертация RDF в другие форматы

Несмотря на то, что RDF расширение имеет большое число самых разнообразных исполнений и модификаций, его конвертация в другие форматы поддерживается только в ряде случаев, в частности:

- если RDF расширение выступает в качестве проекта для моделирования источников света, как составляющих целостных систем освещения, то для его преобразования в или может применяться внутренний транслятор САПР ReluxCAD или

Почему именно RDF и в чем его достоинства?

Приходится констатировать, что хотя RDF расширение имеет большое многообразие различных исполнений, оно отнюдь не является столь популярным и востребованным форматом среди обычных пользователей. Однако формат может быть востребован в нескольких узкоспециализированных областях. Он широко используется в качестве:

- платформы для описания web-ресурсов;

- файла цифрового видео-контента для прямой записи непосредственно на оптический носитель;

- компоненты системы автоматизированного проектирования (САПР), специально предназначенной для моделирования источников света, как составляющих целостных систем освещения;

- файла-отчета в ArcGIS (стандартизованной системе статистического учета, используемой различные ГИС-решения);

- крупноформатной таблицы-отчета, используемой в СУБД.

Базовой структурной единицей RDF является коллекция троек (или триплетов), каждый из которых состоит из субъекта, предиката и объекта (S,P,O). Набор триплетов называется RDF-графом. В качестве вершин графа выступают субъекты и объекты, в качестве дуг – предикаты (или свойства). Направление дуги, соответствующей предикату в данной тройке (S,P,O), всегда выбирается так, чтобы дуга вела от субъекта к объекту.

Рис. 17. RDF-тройка.

Каждая тройка представляет некоторое высказывание, увязывающее S, P и O.

Первые два элемента RDF-тройки (Subject, Predicate) идентифицируются при помощи URI.

Объектом может быть как ресурс, имеющий URI, так и RDF-литерал (значение).

RDF-литералы (или символьные константы)

RDF-литералы бывают 2-х видов: типизированные и не типизированные.

Каждый литерал в RDF-графе содержит 1 или 2 именованные компоненты:

Все литералы имеют лексическую (словарную) форму в виде строки символов Unicode.

Простые литералы имеют лексическую форму и необязательную ссылку на язык (ru, en…).

Типизированные литералы имеют лексическую форму и URI типа данных в форме RDF URI.

Замечание . Язык литерала не нужно путать с идентификатором локали. Языка относится только к текстам, написанным на естественном языке. Все трудности, возникающие при представлении данных на конкретном компьютере (при определении локали), должны решаться конечным пользователем.

Сравнение литералов

Два литерала равны тогда и только тогда, когда выполняются все перечисленные ниже условия:

1. Строки обеих лексических форм совпадают посимвольно;

2. Либо оба литерала имеют теги языка, либо оба не имеют;

3. Теги языка, если они имеются, совпадают;

4. Либо оба литерала имеют URI типа данных, либо оба не имеют;

5. При наличии URI типа данных, эти URI совпадают посимвольно.

Определение значения типизированного литерала

Приведем пример:

Пусть множество {T, F} - множество значений истинности в математической логике. В различных приложениях элементы этого множества могут представляться по-разному. В языках программирования {1, 0} (1 соответствует T, 0 соответствует F), либо {true, false}, либо {истина, ложь}.

Фактически задается некоторое отображение множества значений истинности на множество чисел или строк символов. Теперь значениями логического типа (bool или boolean) в становятся строковые значения или спецсимволы. Чтобы получить значения истинности необходимо воспользоваться обратным отображением.

Таким же образом происходит получение значения типизированного RDF литерала. За лексической формой стоит некоторое значение, которое определяется применением отображения. Это отображение определяется по URI типа данных и зависит от самого типа.

Основы языка представления RDFS.

Каждый из элементов триплета определяется независимо ссылкой на тип элемента и URI.

Предикат (в контексте RDF его обычно называют свойством) может пониматься либо как атрибут, либо как бинарное отношение между двумя ресурсами. Но RDF сам по себе не предоставляет никаких механизмов ни для описания атрибутов ресурсов, ни для определения отношений между ними. Для этого предназначен язык RDFS – (язык описания словарей для RDF). RDF Schema определяет классы, свойства и другие ресурсы.

Рис.18. RDF-тройка субъект-предикат-объект

RDFS является семантическим расширением RDF. Он предоставляет механизмы для описания групп связанных ресурсов и отношений между этими ресурсами. Все определения RDFS выражены на RDF (поэтому RDF и называется «самоописывающимся» языком). Новые термины, вводимые RDFS, такие как «домен», «диапазон» свойства, являются ресурсами RDF.

Оптимизация для улучшения работы поисковых машин и других изощренных инструментов

Обзор

Исторически веб-технологии концентрировались на "впечатлениях и ощущениях", порождаемых веб-страницами и веб-сайтами. Самыми важными были следующие соображения: визуально привлекательный дизайн, ссылки и JavaScript-приложения, работающие надлежащим образом и поддерживающие новейшие мультимедийные функции. Все более важным стало нахождение в верхней части результирующих списков, выдаваемых поисковыми машинами. К сожалению, поисковые машины не видят дизайна веб-сайта и не ощущают динамики его поведения; они видят лишь разметку, которая сводится для них к типу шрифта (полужирный, курсив и т. д.) или к выделению того или иного блока контента.

Часто используемые сокращения

- HTML: HyperText Markup Language

- RDF: Resource Description Framework

- SEO: Search Engine Optimization

Сетевые авторы начали осознавать, что они нуждались в чем-то большем, чем презентационные украшения. Они нуждались в средствах, позволяющих указать поисковой машине или любой другой подобной программе на реальную структуру данных. Например, на то, какая именно информация соответствует цене, дате проведения мероприятия, элементу контактной информации человека и т. д. Существовала потребность в т. н. "сети данных", удовлетворение которой на протяжении долгого времени являлось основной заботой разработчиков модели RDF (Resource Description Framework).

Концепция RDF весьма проста, однако, к сожалению, многие ее аспекты слишком сложны при описании, обсуждении и обработке. Применительно к веб-технологиям типичная рекомендация звучит следующим образом: "Убедитесь в том, что обычный сетевой автор сможет изучить предлагаемую технологию за один день". Для решения этой задачи потребовалось много лет, однако теперь, наконец, появилась разновидность RDF, которая успешно проходит этот тест, а именно RDFa 1.1 Lite.

RDFa Lite — это упрощенная версия RDFa (RDF annotations). RDFa представляет собой механизм для кодирования полной модели данных RDF в рамках HTML и подобных словарей. Сложность модели RDFa несколько превышает пороговое требование "возможность изучения за один день", поэтому группа WHAT WG (которая создала HTML5) создала HTML-спецификацию под названием Microdata. Спецификация Microdata стала ядром Schema.org (см. раздел ), — инициативы по кодификации способов разметки данных в сети. Со временем спецификация Microdata получила статус W3C Working Draft (действующий проект)(см. раздел ), однако защитники RDF и RDFa считали, они смогли бы продвигать RDFa, если бы у них имелось подмножество RDFa, столь же простое как и Microdata. И вот, наконец, мы получили преимущества отработанной модели данных, но с простым синтаксисом.

В прошлом году основатели Schema.org провели семинар для сообщества специалистов по структурированным веб-данным. Я посетил этот семинар, на котором Бен Адида (Ben Adida), редактор спецификации RDFa, продемонстрировал нам работу, которую группа RDF Web Applications Working Group выполнила при создании RDFa Lite. Весьма положительные отзывы о предварительной версии этой спецификации вдохновили организацию W3C на интенсификацию дальнейших усилий в этой области. RDFa 1.1 Lite — это весьма лаконичный действующий проект (working draft) от организации W3C (вполне возможно, что к тому моменту, когда вы будете читать этот текст, этот проект уже превратится в официальную рекомендацию W3C).

Прочитав эту статью, вы узнаете о RDFa 1.1 Lite и сможете быстро приступить к созданию HTML-страниц, включенных в сеть данных. Предполагается, что читатель уже имеет представление о HTML.

Атрибуты для уточнения контента

Совместимость

Формат RDFa совместим со спецификациями HTML 4, HTML 5 и XHTML.

RDFa предусматривает разметку структурированных данных в рамках веб-сайта. Вы не сосредотачиваетесь лишь на том, как контент должен выглядеть с точки зрения пользователя. Вы можете пометить дату как дату, имя человека как имя человека, событие как событие, организацию как организацию и т. д. RDFa Lite редуцирует высокий уровень амбиций до простейших вещей, которые вполне способны работать: к HTML или к XHTML добавляется всего пять атрибутов. Машина способна с легкостью интерпретировать эти атрибуты, чтобы извлечь из веб-страницы полезные данные. Если говорить коротко, то это все.

В показан пример "чистого" HTML-кода для онлайновой статьи.

Листинг 1. Чистый HTML-код для онлайновой статьи

Web development > Technical libraryМодель RDF, разработанная консорциумом W3C для веб-метаданных, использует язык XML в качестве синтаксиса для взаимного обмена. Важнейшая цель RDF состоит в упрощении работы автономных агентов, что очистило бы Интернет посредством совершенствования поисковых машин и сервисных каталогов. Для получения дополнительной информации об RDF прочитайте документ (developerWorks, декабрь 2000 г.).

В оставшейся части этой статьи аннотации HTML-кода в будут рассмотрены с целью демонстрации всех пяти атрибутов спецификации RDFa Lite: vocab , typeof , property , resource , prefix .

Листинг 2. HTML-код для демонстрации RDFa Lite

Атрибут vocab

В показано изменение элемента body с целью упаковки описания всей статьи.

Листинг 3. Использование атрибута vocab

...Атрибут vocab готовит почву в RDFa Lite. Он указывает на словарь, который по умолчанию будет использоваться в аннотациях. В нашем примере используется словарь, соответствующий стандарту Schema.org, поэтому мы выбираем элемент типа wrapper (упаковщик), чтобы пометить его надлежащим образом. У вас нет необходимости использовать элемент body , однако вам следует использовать элемент, который упаковывает все аннотации.

Атрибут typeof

В shows the outline of a div to enclose the one article being described.

Листинг 4. Использование атрибута typeof

Атрибут typeof помечает свой элемент как описание или как представление экземпляра заданного класса. Посредством обозначения vocab , заданного стандартом Schema.org , этот элемент помещается в соответствующий контекст, в результате чего становится ясно, с каким определением "article" (статья) мы имеем дело. Article — это один из классов, специфицированных стандартом Schema.org. Каждое определение класса документировано, в том числе соглашения по его использованию и ассоциированные с ним свойства.

Атрибут property

В показан фрагмент, размечающий заголовок статьи.

Листинг 5. Использование атрибута property

Атрибут property предоставляет свойство объекта, который только что был декларирован как объект Article стандарта Schema.org . Свойство name был задано для того, чтобы дать заголовок этому объекту Article .

В показаны первые три атрибута RDFa Lite.

Листинг 6. Три атрибута RDFa Lite

...В демонстрируются способ, посредством которого RDFa сообщает показанную ниже информацию таким образом, чтобы ее смогла обработать машина.

Данный HTML-документ представляет собой статью, соответствующую спецификации Schema.org, с заголовком "An introduction to RDF" (Введение в RDF)Более изощренные утверждения

Спецификация HTML уже предоставляет доступное для машинной обработки место для размещения заголовка статьи — в элементе head . Однако словарь Schema.org позволяет нам сообщить о статье гораздо больше информации, чем один лишь заголовок, в том числе конструкты, выходящие за рамки HTML (и действительно, на момент написания статьи этот словарь содержал 46 свойств). Даже в случае таких свойств, как заголовок, возможности HTML не всегда оказывались достаточными. Представьте себе, что у вас есть страница, включающая индекс статей, или начальная страницы с результатами поиска. Вам пришлось бы на одной HTML-странице описать несколько реальных статей. HTML не располагает никакими возможностями на этот случай, однако Schema.org позволяет нам иметь несколько элементов div — по одному для каждой статьи, на которую производится ссылка.

Атрибут resource

Если вы способны описать на одной странице несколько объектов, то становится важной возможность предоставить каждому из этих объектов соответствующий идентификатор. RDFa предоставляет для этой цели атрибут resource . В показан фрагмент, аннотирующий автора статьи.

Листинг 7. Атрибут resource

Uche Ogbuji, Partner, Zepheira. 01 Dec 2000.

Данный фрагмент добавляет информацию о том, что "Автор данной статьи — это человек по имени Uche Ogbuji, который является компаньоном в компании Zepheira". Обратите внимание на то, как p элемент был помечен в качестве описания нового объекта типа Person согласно Schema.org. Кроме того, элемент p имеет элемент property , который соединяет этот объект с объектом, заключающим в себе статью.

Атрибут resource предоставляет объекту, описанному в элементе p, идентификатор, который идентифицирует соответствующий фрагмент по отношению к URL-указателю самой страницы. Например, если эта страница находится по адресу http://www.сайт/developerworks/library/w-rdf, то теперь существует объект, который имеет идентификатор http://www..ogbuji.

Zepheira — это организация. В качестве дальнейшего развития этого примера мы можем выразить Zepheira как еще один вложенный объект, используя для этого класс Organization , описанный в спецификации Schema.org. RDFa позволяет нам аннотировать все, что мы считаем важным. В данном случае нас интересуют более подробные сведения об авторе, а не об организации, в которой он работает.

Атрибут prefix

Заключительный атрибут, описанный в спецификации RDFa Lite — prefix — используется для объединения нескольких словарей в одном описании.В показано, каким образом можно аннотировать индекс "читабельности" статьи.

Листинг 8. Атрибут prefix

Спецификация Schema.org не содержит свойства для индекса читабельности текста Gunning-Fog — в отличие от Freebase. Freebase — несколько более структурированная разновидность Wikipedia — управляет схемами и описаниями для широкого разнообразия объектов и типов объектов. Я задал префикс для ссылки на свойства согласно спецификациям Freebase, а не словарю Schema.org по умолчанию, а затем использовал этот префикс для текста, представляющего собой значение индекса читабельности для данной статьи.

Обобщающий пример

В сведены воедино все продемонстрированные к настоящему моменту элементы, а также добавлены такие элементы, как breadcrumb.

Листинг 9. Использование всех пяти атрибутов RDFa Lite

...By Uche Ogbuji, Partner, Zepheira.

С точки зрения структуры здесь нет ничего нового, однако в показано несколько других свойств Schema.org, которые вы сможете использовать для какой-либо статьи.

Заключение

Помимо Schema.org существуют и другие словари, в том числе Dublin Core (имеющий базовую поддержку в RDFa) и Facebook Social Open Graph. Тем не менее, стандарт Schema.org в последнее время получил мощную поддержку, особенно с учетом своих выдающихся апологетов. Это новейшее достижение в длинном перечне событий в такой сфере, как оптимизация поисковых механизмов (search-engine optimization, SEO).

Вполне возможно, что идея SEO имеет преимущественно маркетинговый характер, однако она полностью базируется на таких концепциях совершенствования веб-технологий, как достижимость, чистая разметка и аннотирование страниц — везде, где это возможно, и с привлечением большего количества информации о фактическом значении контента. Такие достижения, как RDFa Lite, призваны разместить мощные возможности SEO в пределах досягаемости практически любого сетевого автора. Я надеюсь, что эта статья поможет вам изучить RDFa за один день и призывают вас немедленно приступить к аннотированию своих страниц.